"Marc Chagall and the Paris Opera", the story of an eyewitness

When Marc Chagall painted the ceiling of the Paris opera in 1964, he became the target of foreigners' haters and anti-Semites. The Dutch artist Paul Versteeg was there.

"We had to complete our work under police protection. It is amazing how the French offend foreigners. You live here for most of your life. You become a national of French citizens, you give them twenty paintings for their museum of modern art, you work on decorating their cathedrals for nothing and they still despise you".

It is the mid-sixties and Marc Chagall is speaking with art critic Carlton Lake. The artist has just completed one of his most prestigious commissions: the painting of the ceiling of the Paris Opéra. The work was successful and Chagall is happy. But he is also disappointed, because for some French people he is still a foreigner. A Russian, or even worse, a Jewish Russian. And they say he should stay away from the national French heritage.

Marc Chagall treated like an immigrant

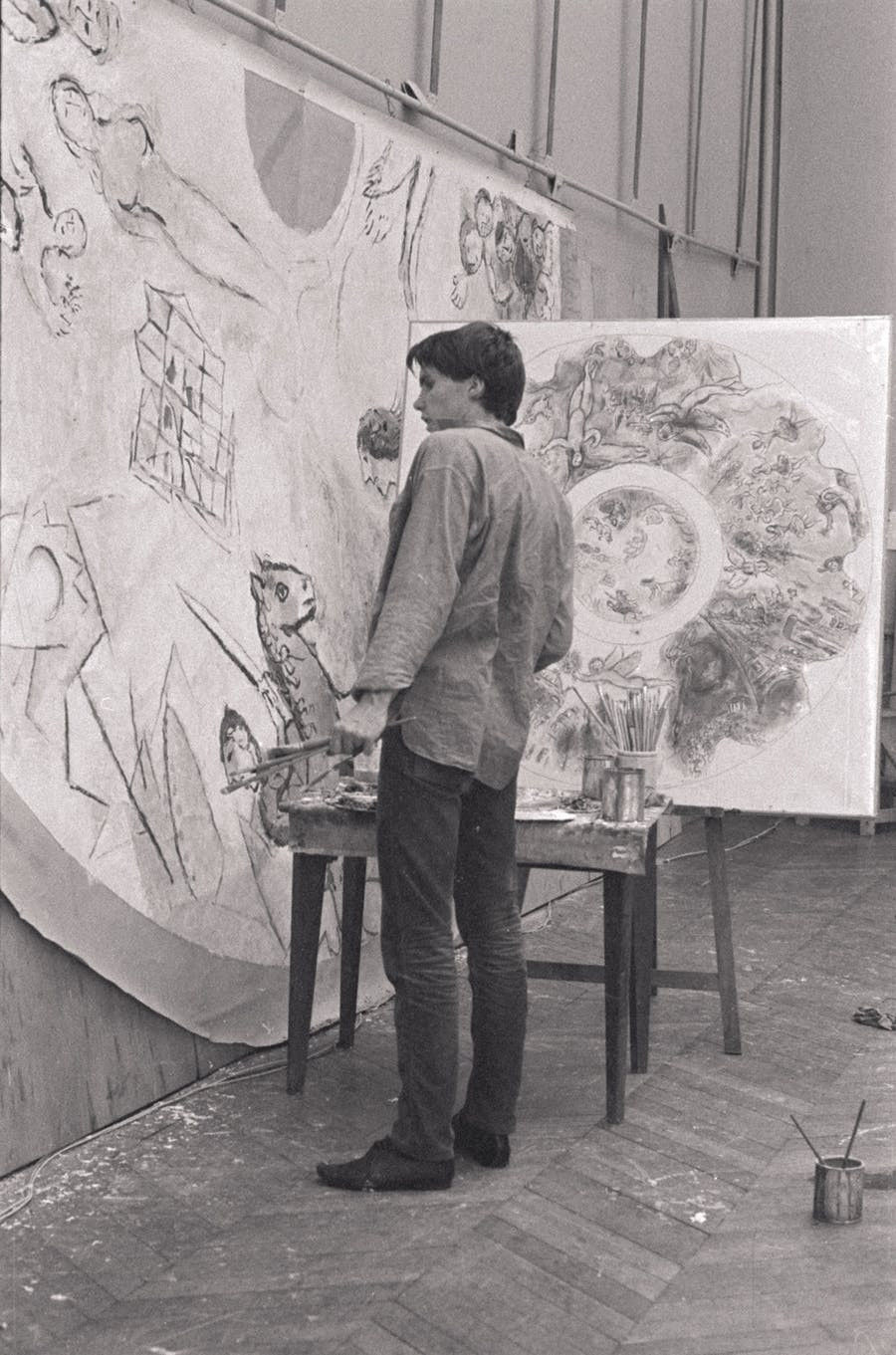

The Dutch artist Paul Versteeg (75) experienced that turbulent episode from nearby, he tells in the Stedelijk Museum. There is currently an exhibition devoted to immigrant stories, by Chagall and other artists who moved to the city of lights at the beginning of the last century. He saw a violent polemic around Marc Chagall As a twenty-year-old boy, Versteeg helped Chagall with the ceiling of the opera. "Just like many great artists in the past, he had this work painted," says Versteeg. "Then Chagall finished the work himself." Versteeg saw a violent polemic around Marc Chagall, with a toxic, Anti-Semitic undertone. "Chagall tried to stay away from that," the Dutch artist recalls. "He was avoiding the issue but of course those comments touched him. You cannot let that slip away. " It was the French minister of culture, André Malraux, who had askedMarc Chagall to paint the ceiling of the Paris Opéra Garnier. The opera house, designed by Charles Garnier in 1860, a lavish mix of tinsel and marble. Garnier had devised that style himself and called it Napoleon III, as a tribute to the man who was then emperor of France.

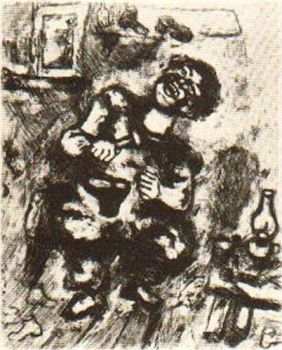

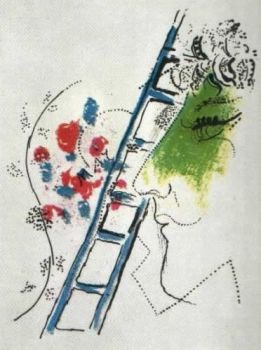

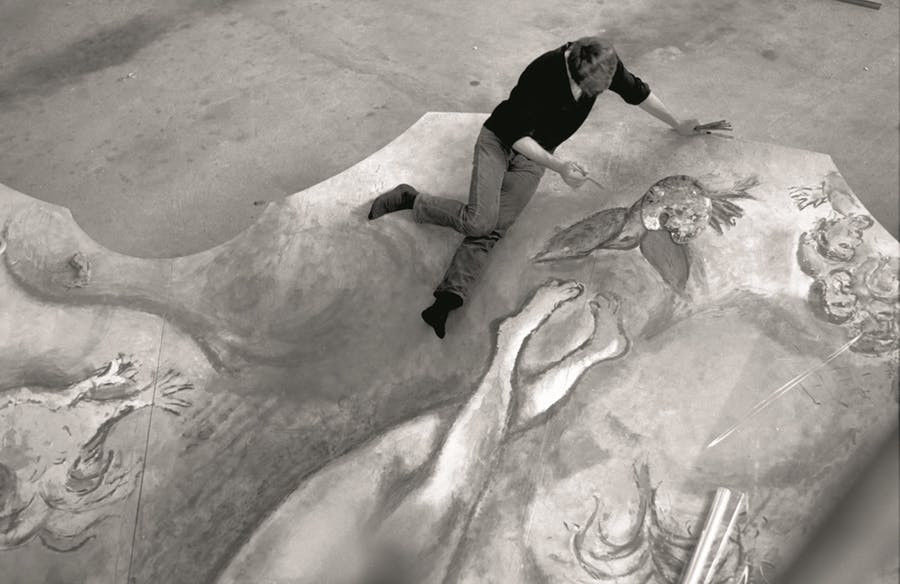

Paul Versteegh assisting Marc Chagall with his work in the Paris Opera

When in the summer of 1963 it became known that Marc Chagall would paint the ceiling, a shock went through the conservative circles in France. "It is as if Minister Malraux had ordered the Eiffel Tower to be painted pink," wrote the correspondent of The Los Angeles Times. The reaction of the conservative newspaper Le Figaro was typical: "It would be a bad taste to question Marc Chagall's immense talent," said the newspaper's art critic. "But that talent, strongly influenced by the taste of the 1920s, can only clash with the tinsel and the decorations of the Palais Garnier." That response was civilized. You can argue about taste. And there was indeed a gap between the lavish mix of gold and marble in the opera house and the loose, colorful style of Marc Chagall. But others went further and were angry that someone from the Russian ghetto would touch the French national heritage with his fingers.

Hard to keep up with Marc Chagall

In the midst of that controversy, Paul Versteeg arrived in Paris. A child of artistic parents, raised in southern France and with three years of art school. "That academy was not for me. Not modern enough, he says". Versteeg wanted to stop the academy and told Charles Marq, a friend of the family and also the stained-glass artist who made his stained-glass windows for Chagall. "Marq then asked if I wanted to work for Chagall. I was shocked. Could I do that? " But a few months later, Versteeg got off the train in Paris and joined the Chagall team. He was already 78 at the time, but there was not much evidence of that old age. "We couldn't keep up with him physically. He worked at a high pace and had enormous stamina, "Versteeg remembers. "Marc Chagall came into the studio at nine o'clock in the morning, then worked up a sweat for an hour and a half, went to shower, then to work again and then to have lunch. And in the afternoon he did it again, squatting, stooping, crawling.

Paul Versteegh assisting Marc Chagall with his work in the Paris Opera

This was the greatest work that Marc Chagall had made until then. It took courage to start on that. "It was a one-off opportunity, but with a big risk," Versteeg explains. "It could be a success, but he could also be sabbed down." That led to stress. The occasional strong xenophobic wind blowing outside the walls of the workplace also didn't help. As a young student, Versteeg did not dare to ask Marc Chagall what he thought of that. "But of course I felt it struck him". Anti-Semitism was no stranger to Marc Chagall.

The cruel journey of Marc Chagall

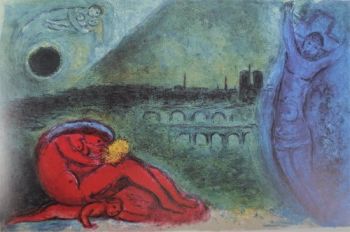

He was born in 1887 as the son of Hasidic Jewish parents in the Russian city of Vitebsk, which is now located in Belarus. Anti-Semitism was ubiquitous in the Russian Empire, Jews were second-class citizens. In his autobiography, My Life, Marc Chagall writes laconically about it. For example about when his mother tried to get him into public school. "But they don't allow Jews at this school. My mother approached the teacher without hesitation (...) Fifty rubles, that's not much. I was in third grade right away. "After coming to Paris in 1910, Chagall went back to Russia again In the Second World War, anti-Semitism became infinitely more painful. Marc Chagall had fled to Nice via Nice, but his family in Vitebsk were trapped. In 1941 the Wehrmacht conquered the city. The Jewish community where Marc Chagall grew up was locked up in the ghetto. Almost everyone was killed. After arriving in Paris in 1910, Marc Chagall had returned to Russia again. On the eve of the First World War he married his childhood sweetheart, Bella Rosenfeld. "But now there was nothing left of the Vitebsk of his youth," says Versteeg. "All destroyed." When the Nazis were driven out, Marc Chagall returned to Paris. Only, because his wife had died of a virus infection in the US. Paris was his home. Over the course of time, he felt completely French and nationalized. Marc Chagall was officially no longer a foreigner, but Versteeg was when he was painting the ceiling in Paris. This led to friction with the clients, the French Ministry of Culture.

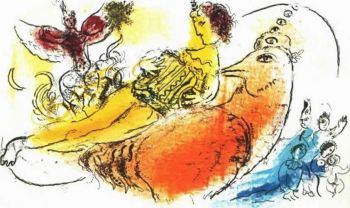

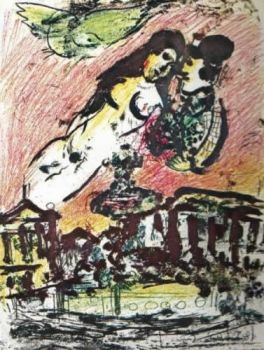

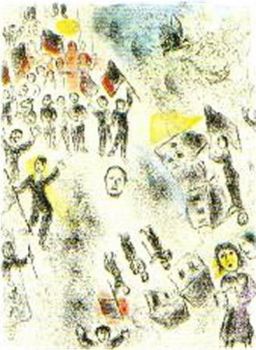

Marc Chagall and the finished work at the Paris Opera

Controversial work in difficult circumstances

"I only got paid after a lot of hassle. As a minor they could not give me a contract and as a foreigner I could not open a bank account, says Versteeg". "At the ministry I was told that I should consider it as an honor that I was allowed to work on the ceiling of the opera. They also asked if there were any French people who could do my job. Then you really feel like an immigrant. " "Fortunately my father advanced the money and there was someone at BNP Paribas who opened a fake account for me," Versteeg continues. "I remember the number: M30. I was able to withdraw money with it in France, England and Italy. " That way he could continue to cooperate and he also experienced the hectic final weeks. The existing ceiling painting in the opera, a traditional work by Jules Eugène Lenepveu, would be spared. The much more modern work of Chagall was, as it were, hung under it. When the pieces of cloth were ready, they were transferred to a military site. There they were mounted on a frame. The guards were standing outside with stenguns to keep malicious people out. Here Versteeg saw how much the controversial painting brought about. "There were guards with stenguns outside," he recalls. They not only had to keep malicious people - right-wing creeps, as Versteeg calls them - outside, but also keep the curious press at bay. Because of all the fuss, which has now lasted more than a year, the outside world had become extremely curious about the artwork. The work was unveiled on September 23rd, 1964. The reactions were mixed, as was to be expected. The assignment had brought Marc Chagall even more fame, but also a scratch on his soul. Once a foreigner, always a foreigner, had once again become clear to him. Or in his own words: "You are not one of them. It has always been that way". Yet Marc Chagall never charged a cent for the work. He saw it as a gift to his second home country, although he did retain the image rights. And Versteeg? He decided to finish the old-fashioned Rijksakademie. "The great painters I had met worked very modernly, but they had all finished the academy."

Chagall, Picasso, Mondriaan and others. - Migrants in Paris, Chagall Exhibition in the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam, to be seen until 2 February 2020.

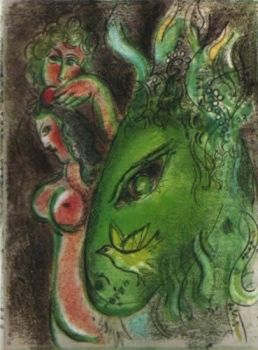

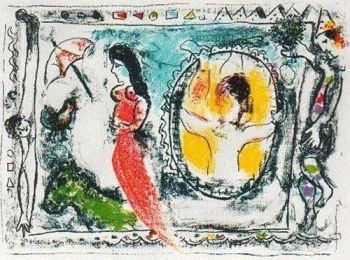

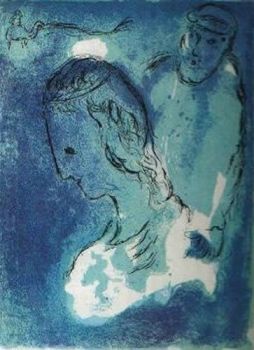

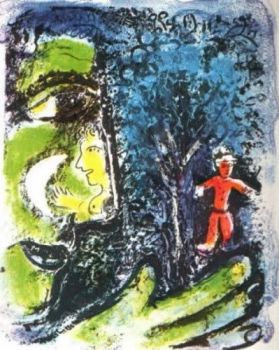

Interested in buying a litho of Marc Chagall? Please have a look at our website, Gallerease for available works of Chagall!

Interested in buying a litho of Picasso? Please have a look at our website, Gallerease for available works of Picasso!